In the ‘Wandering Rocks’ episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Leopold Bloom visits a dingy bookshop in search for some titillating literature to take back home to Molly.

Among the titles he casts aside are The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk and Aristotle’s Masterpiece with its ‘[c]rooked botched print’.1 The latter is a pregnancy and midwifery manual first published in the seventeenth century – not authored by Aristotle. The former is a sensationalist memoir by one ‘Maria Monk’, claiming to be a true account of the abuses suffered by her and other nuns in a Catholic convent in Montreal, first published in New York in 1836.

I recently came across a copy of this book in a second-hand bookshop in Totnes (more charmingly chaotic than dingy) and, remembering the scene from Ulysses, had to bring it home.

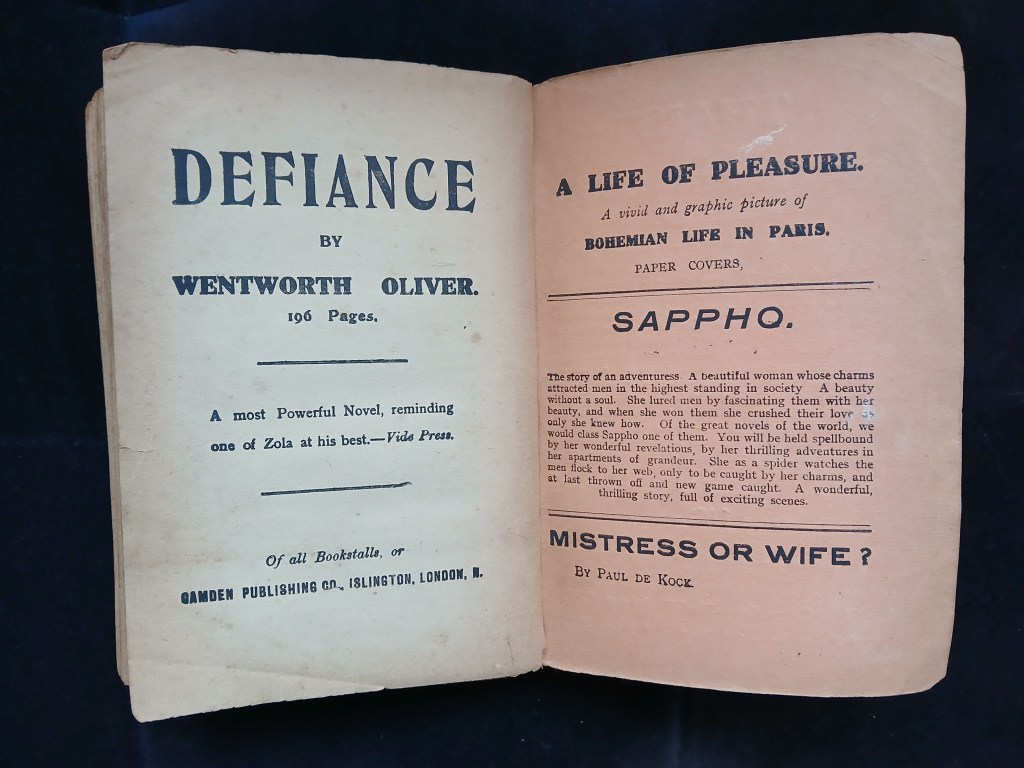

The Edition is undated but probably Early twentieth-century, published by the ‘Camden Publishing Company, a somewhat mysterious outfit apparently based in Islington.

The printing is fantastically poor quality, and, being an ‘illustrated’ version of Monk’s Tale, the book is peppered throughout with equally poorly printed plates bearing little to no relation to the contents of the text.

Most intriguing in relation to the mention of Maria monk in ‘Wandering Rocks’, however, is another aspects of the book’s Peritext: the cross-advertisements for other titles published by the Camden Publishing co. that we find at the beginning and end of the book.

If, in the mid-nineteenth century, Maria Monk was read and distributed above all as a sensationalist memoir and anti-catholic polemic, by the time of the Camden Publishing Co. Edition it had clearly become incorporated into a somewhat different publishing culture, evolving around the distribution of salacious literature.

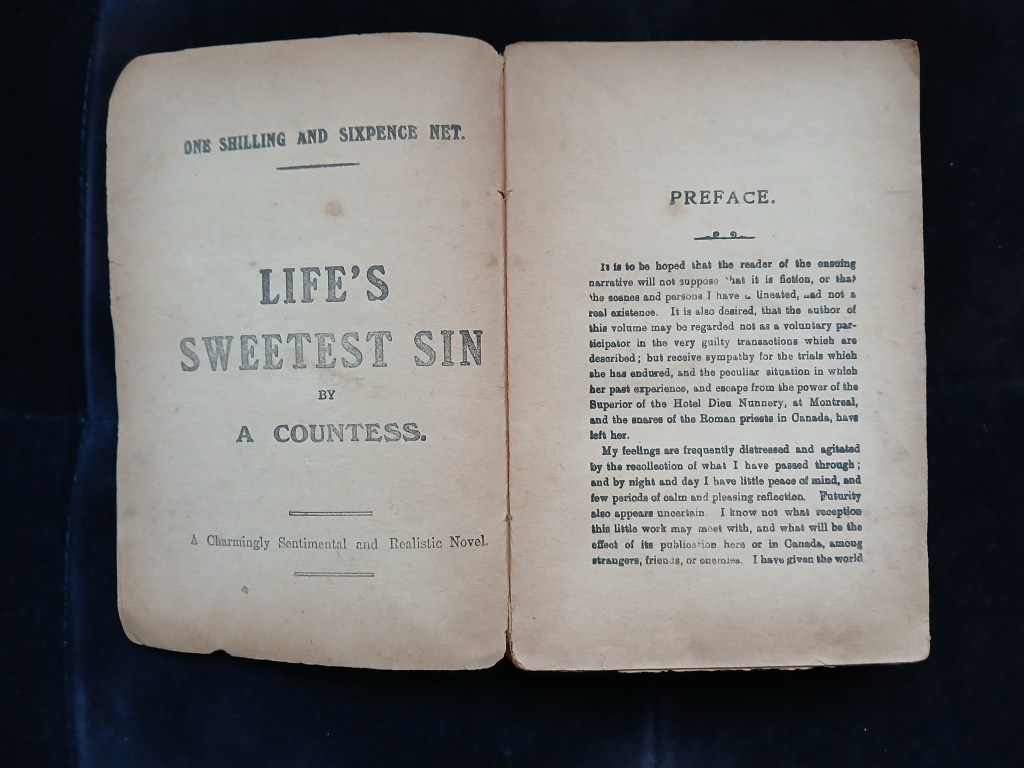

The most evocative of these advertisements is for a book called Life’s Sweetest sin, a ‘Charmingly sentimental and realistic novel’ by ‘A Countess’, whose title is strongly reminiscent of Joyce’s Sweets of Sin, the book that Bloom eventually ends up buying for Molly in ‘Wandering Rocks’.

Could Joyce have taken inspiration from this advert for the title of his own Fictional Erotic Tale about a ‘beautiful woman’ with ‘queenly shoulders’ and her lover ‘Raoul’?2 It seems not entirely unlikely.

He certainly was a bad, bad reader …

1 James Joyce, Ulysses: The 1922 Text, ed. by Jeri Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 226.

2 Ibid.